University of Duisburg-Essen, House of Energy, Climate, and Finance

2025-06-30

\[ \newcommand{\A}{{\mathbb A}} \]

Artwork by @allison_horst

| Energy market liberalization created complex, interconnected trading systems | |

| Renewable energy transition introduces uncertainty and volatility from weather-dependent generation | |

| Traditional point forecasts are inadequate for modern energy markets with increasing uncertainty | |

| Risk inherently is a probabilistic concept | |

| Probabilistic forecasting essential for risk management, planning and decision making in volatile energy environments | |

| Online learning methods needed for fast-updating models with streaming energy data |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2023). CRPS learning. Journal of Econometrics, 237(2), 105221. | |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2024). Multivariate probabilistic CRPS learning with an application to day-ahead electricity prices. International Journal of Forecasting, 40(4), 1568–1586. | |

| Hirsch, S., Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2024). Online Distributional Regression. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08750. | |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2022). Distributional modeling and forecasting of natural gas prices. Journal of Forecasting, 41(6), 1065–1086. | |

| Berrisch, J., Pappert, S., Ziel, F., & Arsova, A. (2023). Modeling volatility and dependence of European carbon and energy prices. Finance Research Letters, 52, 103503. | |

| Berrisch, J., Narajewski, M., & Ziel, F. (2023). High-resolution peak demand estimation using generalized additive models and deep neural networks. Energy and AI, 13, 100236. | |

| Berrisch, J. (2025). rcpptimer: Rcpp Tic-Toc Timer with OpenMP Support. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.15856. |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2023). CRPS learning. Journal of Econometrics, 237(2), 105221. | |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2024). Multivariate probabilistic CRPS learning with an application to day-ahead electricity prices. International Journal of Forecasting, 40(4), 1568–1586. | |

| Hirsch, S., Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2024). Online Distributional Regression. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08750. | |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2022). Distributional modeling and forecasting of natural gas prices. Journal of Forecasting, 41(6), 1065–1086. | |

| Berrisch, J., Pappert, S., Ziel, F., & Arsova, A. (2023). Modeling volatility and dependence of European carbon and energy prices. Finance Research Letters, 52, 103503. | |

| Berrisch, J., Narajewski, M., & Ziel, F. (2023). High-resolution peak demand estimation using generalized additive models and deep neural networks. Energy and AI, 13, 100236. | |

| Berrisch, J. (2025). rcpptimer: Rcpp Tic-Toc Timer with OpenMP Support. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.15856. |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2023). CRPS learning. Journal of Econometrics, 237(2), 105221. | |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2024). Multivariate probabilistic CRPS learning with an application to day-ahead electricity prices. International Journal of Forecasting, 40(4), 1568–1586. | |

| Hirsch, S., Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2024). Online Distributional Regression. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08750. | |

| Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2022). Distributional modeling and forecasting of natural gas prices. Journal of Forecasting, 41(6), 1065–1086. | |

| Berrisch, J., Pappert, S., Ziel, F., & Arsova, A. (2023). Modeling volatility and dependence of European carbon and energy prices. Finance Research Letters, 52, 103503. | |

| Berrisch, J., Narajewski, M., & Ziel, F. (2023). High-resolution peak demand estimation using generalized additive models and deep neural networks. Energy and AI, 13, 100236. | |

| Berrisch, J. (2025). rcpptimer: Rcpp Tic-Toc Timer with OpenMP Support. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.15856. |

Reduces estimation time by 2-3 orders of magnitude

Maintainins competitive forecasting accuracy

Real-World Validation in Energy Markets

Predict high-resolution electricity peaks using only low-resolution data

Combine GAMs and DNN’s for superior accuracy

Won Western Power Distribution Competition

Won Best-Student-Presentation Award

Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2023). Journal of Econometrics, 237(2), 105221.

The Idea:

Combine multiple forecasts instead of choosing one

Combination weights may vary over time, over the distribution or both

2 Popular options for combining distributions:

Each day, \(t = 1, 2, ... T\)

Weights are updated sequentially according to the past performance of the \(K\) experts.

That is, a loss function \(\ell\) is needed. This is used to compute the cumulative regret \(R_{t,k}\)

\[\begin{equation} R_{t,k} = \widetilde{L}_{t} - \widehat{L}_{t,k} = \sum_{i = 1}^t \ell(\widetilde{X}_{i},Y_i) - \ell(\widehat{X}_{i,k},Y_i)\label{eq:regret} \end{equation}\]

The cumulative regret:

Popular loss functions for point forecasting Gneiting (2011):

\(\ell_2\) loss:

\[\begin{equation} \ell_2(x, y) = | x -y|^2 \label{eq:elltwo} \end{equation}\]

Strictly proper for mean prediction

\(\ell_1\) loss:

\[\begin{equation} \ell_1(x, y) = | x -y| \label{eq:ellone} \end{equation}\]

Strictly proper for median predictions

\[\begin{equation} w_{t,k}^{\text{Naive}} = \frac{1}{K}\label{eq:naive_combination} \end{equation}\]

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} w_{t,k}^{\text{EWA}} & = \frac{e^{\eta R_{t,k}} }{\sum_{k = 1}^K e^{\eta R_{t,k}}}\\ & = \frac{e^{-\eta \ell(\widehat{X}_{t,k},Y_t)} w^{\text{EWA}}_{t-1,k} }{\sum_{k = 1}^K e^{-\eta \ell(\widehat{X}_{t,k},Y_t)} w^{\text{EWA}}_{t-1,k}} \end{aligned}\label{eq:exp_combination} \end{equation}\]

In stochastic settings, the cumulative Risk should be analyzed Wintenberger (2017): \[\begin{align} &\underbrace{\widetilde{\mathcal{R}}_t = \sum_{i=1}^t \mathbb{E}[\ell(\widetilde{X}_{i},Y_i)|\mathcal{F}_{i-1}]}_{\text{Cumulative Risk of Forecaster}} \\ &\underbrace{\widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,k} = \sum_{i=1}^t \mathbb{E}[\ell(\widehat{X}_{i,k},Y_i)|\mathcal{F}_{i-1}]}_{\text{Cumulative Risk of Experts}} \label{eq_def_cumrisk} \end{align}\]

\[\begin{equation} \frac{1}{t}\left(\widetilde{\mathcal{R}}_t - \widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\min} \right) \stackrel{t\to \infty}{\rightarrow} a \quad \text{with} \quad a \leq 0. \label{eq_opt_select} \end{equation}\] The forecaster is asymptotically not worse than the best expert \(\widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\min}\).

\[\begin{equation} \frac{1}{t}\left(\widetilde{\mathcal{R}}_t - \widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\pi} \right) \stackrel{t\to \infty}{\rightarrow} b \quad \text{with} \quad b \leq 0 . \label{eq_opt_conv} \end{equation}\] The forecaster is asymptotically not worse than the best convex combination \(\widehat{X}_{t,\pi}\) in hindsight (oracle).

Optimal rates with respect to selection \(\eqref{eq_opt_select}\) and convex aggregation \(\eqref{eq_opt_conv}\) Wintenberger (2017):

\[\begin{align} \frac{1}{t}\left(\widetilde{\mathcal{R}}_t - \widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\min} \right) & = \mathcal{O}\left(\frac{\log(K)}{t}\right)\label{eq_optp_select} \end{align}\]

\[\begin{align} \frac{1}{t}\left(\widetilde{\mathcal{R}}_t - \widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\pi} \right) & = \mathcal{O}\left(\sqrt{\frac{\log(K)}{t}}\right) \label{eq_optp_conv} \end{align}\]

Algorithms can statisfy both \(\eqref{eq_optp_select}\) and \(\eqref{eq_optp_conv}\) depending on:

EWA satisfies optimal selection convergence \(\eqref{eq_optp_select}\) in a deterministic setting if:

Those results can be converted to any stochastic setting Wintenberger (2017).

Optimal convex aggregation convergence \(\eqref{eq_optp_conv}\) can be satisfied by applying the kernel-trick:

\[\begin{align} \ell^{\nabla}(x,y) = \ell'(\widetilde{X},y) x \end{align}\]

\(\ell'\) is the subgradient of \(\ell\) at forecast combination \(\widetilde{X}\).

An appropriate choice:

\[\begin{equation*} \text{CRPS}(F, y) = \int_{\mathbb{R}} {(F(x) - \mathbb{1}\{ x > y \})}^2 dx \label{eq:crps} \end{equation*}\]

It’s strictly proper Gneiting & Raftery (2007).

Using the CRPS, we can calculate time-adaptive weights \(w_{t,k}\). However, what if the experts’ performance varies in parts of the distribution?

Utilize this relation:

\[\begin{equation*} \text{CRPS}(F, y) = 2 \int_0^{1} \text{QL}_p(F^{-1}(p), y) dp.\label{eq_crps_qs} \end{equation*}\]

… to combine quantiles of the probabilistic forecasts individually using the quantile-loss QL.

QL is convex, but not exp-concave

Bernstein Online Aggregation (BOA) lets us weaken the exp-concavity condition. It satisfies that there exist a \(C>0\) such that for \(x>0\) it holds that

\[\begin{equation} P\left( \frac{1}{t}\left(\widetilde{\mathcal{R}}_t - \widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\pi} \right) \leq C \log(\log(t)) \left(\sqrt{\frac{\log(K)}{t}} + \frac{\log(K)+x}{t}\right) \right) \geq 1-e^{-x} \label{eq_boa_opt_conv} \end{equation}\]

Almost optimal w.r.t. convex aggregation \(\eqref{eq_optp_conv}\) Wintenberger (2017).

The same algorithm satisfies that there exist a \(C>0\) such that for \(x>0\) it holds that \[\begin{equation} P\left( \frac{1}{t}\left(\widetilde{\mathcal{R}}_t - \widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\min} \right) \leq C\left(\frac{\log(K)+\log(\log(Gt))+ x}{\alpha t}\right)^{\frac{1}{2-\beta}} \right) \geq 1-2e^{-x} \label{eq_boa_opt_select} \end{equation}\]

if \(Y_t\) is bounded, the considered loss \(\ell\) is convex \(G\)-Lipschitz and weak exp-concave in its first coordinate.

Almost optimal w.r.t. selection \(\eqref{eq_optp_select}\) Gaillard & Wintenberger (2018).

We show that this holds for QL under feasible conditions.

Lemma 1

\[\begin{align} 2\overline{\widehat{\mathcal{R}}}^{\text{QL}}_{t,\min} & \leq \widehat{\mathcal{R}}^{\text{CRPS}}_{t,\min} \label{eq_risk_ql_crps_expert} \\ 2\overline{\widehat{\mathcal{R}}}^{\text{QL}}_{t,\pi} & \leq \widehat{\mathcal{R}}^{\text{CRPS}}_{t,\pi} . \label{eq_risk_ql_crps_convex} \end{align}\]

Pointwise can outperform constant procedures

QL is convex but not exp-concave:

Almost optimal convergence w.r.t. convex aggregation \(\eqref{eq_boa_opt_conv}\)

For almost optimal congerence w.r.t. selection \(\eqref{eq_boa_opt_select}\) we need to check A1 and A2:

QL is Lipschitz continuous:

A1 holds

A1

For some \(G>0\) it holds for all \(x_1,x_2\in \mathbb{R}\) and \(t>0\) that

\[ | \ell(x_1, Y_t)-\ell(x_2, Y_t) | \leq G |x_1-x_2|\]

A2 For some \(\alpha>0\), \(\beta\in[0,1]\) it holds for all \(x_1,x_2 \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(t>0\) that

\[\begin{align*} \mathbb{E}[ & \ell(x_1, Y_t)-\ell(x_2, Y_t) | \mathcal{F}_{t-1}] \leq \\ & \mathbb{E}[ \ell'(x_1, Y_t)(x_1 - x_2) |\mathcal{F}_{t-1}] \\ & + \mathbb{E}\left[ \left. \left( \alpha(\ell'(x_1, Y_t)(x_1 - x_2))^{2}\right)^{1/\beta} \right|\mathcal{F}_{t-1}\right] \end{align*}\]

Almost optimal w.r.t. selection \(\eqref{eq_optp_select}\) Gaillard & Wintenberger (2018).

Conditional quantile risk: \(\mathcal{Q}_p(x) = \mathbb{E}[ \text{QL}_p(x, Y_t) | \mathcal{F}_{t-1}]\).

convexity properties of \(\mathcal{Q}_p\) depend on the conditional distribution \(Y_t|\mathcal{F}_{t-1}\).

Proposition 1

Let \(Y\) be a univariate random variable with (Radon-Nikodym) \(\nu\)-density \(f\), then for the second subderivative of the quantile risk \(\mathcal{Q}_p(x) = \mathbb{E}[ \text{QL}_p(x, Y) ]\) of \(Y\) it holds for all \(p\in(0,1)\) that \(\mathcal{Q}_p'' = f.\) Additionally, if \(f\) is a continuous Lebesgue-density with \(f\geq\gamma>0\) for some constant \(\gamma>0\) on its support \(\text{spt}(f)\) then is \(\mathcal{Q}_p\) is \(\gamma\)-strongly convex.

Strong convexity with \(\beta=1\) implies weak exp-concavity A2 Gaillard & Wintenberger (2018)

A1 and A2 give us almost optimal convergence w.r.t. selection \(\eqref{eq_boa_opt_select}\)

Theorem 1

The gradient based fully adaptive Bernstein online aggregation (BOAG) applied pointwise for all \(p\in(0,1)\) on \(\text{QL}\) satisfies \(\eqref{eq_boa_opt_conv}\) with minimal CRPS given by

\[\widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\pi} = 2\overline{\widehat{\mathcal{R}}}^{\text{QL}}_{t,\pi}.\]

If \(Y_t|\mathcal{F}_{t-1}\) is bounded and has a pdf \(f_t\) satifying \(f_t>\gamma >0\) on its support \(\text{spt}(f_t)\) then \(\ref{eq_boa_opt_select}\) holds with \(\beta=1\) and

\[\widehat{\mathcal{R}}_{t,\min} = 2\overline{\widehat{\mathcal{R}}}^{\text{QL}}_{t,\min}\].

Simple Example:

\[\begin{align} Y_t & \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\,1) \\ \widehat{X}_{t,1} & \sim \widehat{F}_{1} = \mathcal{N}(-1,\,1) \\ \widehat{X}_{t,2} & \sim \widehat{F}_{2} = \mathcal{N}(3,\,4) \label{eq:dgp_sim1} \end{align}\]

Penalized cubic B-Splines for smoothing weights:

Let \(\varphi=(\varphi_1,\ldots, \varphi_L)\) be bounded basis functions on \((0,1)\) Then we approximate \(w_{t,k}\) by

\[\begin{align} w_{t,k}^{\text{smooth}} = \sum_{l=1}^L \beta_l \varphi_l = \beta'\varphi \end{align}\]

with parameter vector \(\beta\). The latter is estimated to penalize \(L_2\)-smoothing which minimizes

\[\begin{equation} \| w_{t,k} - \beta' \varphi \|^2_2 + \lambda \| \mathcal{D}^{d} (\beta' \varphi) \|^2_2 \label{eq_function_smooth} \end{equation}\]

with differential operator \(\mathcal{D}\)

Computation is easy, since we have an analytical solution

We receive the constant solution for high values of \(\lambda\) when setting \(d=1\)

Represent weights as linear combinations of bounded basis functions:

\[\begin{equation} w_{t,k} = \sum_{l=1}^L \beta_{t,k,l} \varphi_l = \boldsymbol \beta_{t,k}' \boldsymbol \varphi \end{equation}\]

A popular choice are are B-Splines as local basis functions

\(\boldsymbol \beta_{t,k}\) is calculated using a reduced regret matrix:

\[\begin{equation} \underbrace{\boldsymbol r_{t}}_{\text{LxK}} = \frac{L}{P} \underbrace{\boldsymbol B'}_{\text{LxP}} \underbrace{\left({\boldsymbol{QL}}_{\mathcal{P}}^{\nabla}(\widetilde{\boldsymbol X}_{t},Y_t)- {\boldsymbol{QL}}_{\mathcal{P}}^{\nabla}(\widehat{\boldsymbol X}_{t},Y_t)\right)}_{\text{PxK}} \end{equation}\]

\(\boldsymbol r_{t}\) is transformed from PxK to LxK

If \(L = P\) it holds that \(\boldsymbol \varphi = \boldsymbol{I}\) For \(L = 1\) we receive constant weights

Weights converge to the constant solution if \(L\rightarrow 1\)

Array of expert predicitons: \(\widehat{X}_{t,p,k}\)

Vector of Prediction targets: \(Y_t\)

Starting Weights: \(\boldsymbol w_0=(w_{0,1},\ldots, w_{0,K})\)

Penalization parameter: \(\lambda\geq 0\)

B-spline and penalty matrices \(\boldsymbol B\) and \(\boldsymbol D\) on \(\mathcal{P}= (p_1,\ldots,p_M)\)

Hat matrix: \[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}} = \boldsymbol B(\boldsymbol B'\boldsymbol B+ \lambda (\alpha \boldsymbol D_1'\boldsymbol D_1 + (1-\alpha) \boldsymbol D_2'\boldsymbol D_2))^{-1} \boldsymbol B'\]

Cumulative Regret: \(R_{0,k} = 0\)

Range parameter: \(E_{0,k}=0\)

Starting pseudo-weights: \(\boldsymbol \beta_0 = \boldsymbol B^{\text{pinv}}\boldsymbol w_0(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{P}})\)

for( t in 1:T ) {

\(\widetilde{\boldsymbol X}_{t} = \text{Sort}\left( \boldsymbol w_{t-1}'(\boldsymbol P) \widehat{\boldsymbol X}_{t} \right)\) # Prediction

\(\boldsymbol r_{t} = \frac{L}{M} \boldsymbol B' \left({\boldsymbol{QL}}_{\boldsymbol{\mathcal P}}^{\nabla}(\widetilde{\boldsymbol X}_{t},Y_t)- {\boldsymbol{QL}}_{\boldsymbol{\mathcal P}}^{\nabla}(\widehat{\boldsymbol X}_{t},Y_t)\right)\)

\(\boldsymbol E_{t} = \max(\boldsymbol E_{t-1}, \boldsymbol r_{t}^+ + \boldsymbol r_{t}^-)\)

\(\boldsymbol V_{t} = \boldsymbol V_{t-1} + \boldsymbol r_{t}^{ \odot 2}\)

\(\boldsymbol \eta_{t} =\min\left( \left(-\log(\boldsymbol \beta_{0}) \odot \boldsymbol V_{t}^{\odot -1} \right)^{\odot\frac{1}{2}} , \frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol E_{t}^{\odot-1}\right)\)

\(\boldsymbol R_{t} = \boldsymbol R_{t-1}+ \boldsymbol r_{t} \odot \left( \boldsymbol 1 - \boldsymbol \eta_{t} \odot \boldsymbol r_{t} \right)/2 + \boldsymbol E_{t} \odot \mathbb{1}\{-2\boldsymbol \eta_{t}\odot \boldsymbol r_{t} > 1\}\)

\(\boldsymbol \beta_{t} = K \boldsymbol \beta_{0} \odot \boldsymbol {SoftMax}\left( - \boldsymbol \eta_{t} \odot \boldsymbol R_{t} + \log( \boldsymbol \eta_{t}) \right)\)

\(\boldsymbol w_{t}(\boldsymbol P) = \underbrace{\boldsymbol B(\boldsymbol B'\boldsymbol B+ \lambda (\alpha \boldsymbol D_1'\boldsymbol D_1 + (1-\alpha) \boldsymbol D_2'\boldsymbol D_2))^{-1} \boldsymbol B'}_{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}} \boldsymbol B \boldsymbol \beta_{t}\)

}

Data Generating Process of the simple probabilistic example:

\[\begin{align*} Y_t &\sim \mathcal{N}(0,\,1)\\ \widehat{X}_{t,1} &\sim \widehat{F}_{1}=\mathcal{N}(-1,\,1) \\ \widehat{X}_{t,2} &\sim \widehat{F}_{2}=\mathcal{N}(3,\,4) \end{align*}\]

Deviation from best attainable QL (1000 runs).

CRPS Values for different \(\lambda\) (1000 runs)

CRPS for different number of knots (1000 runs)

The same simulation carried out for different algorithms (1000 runs):

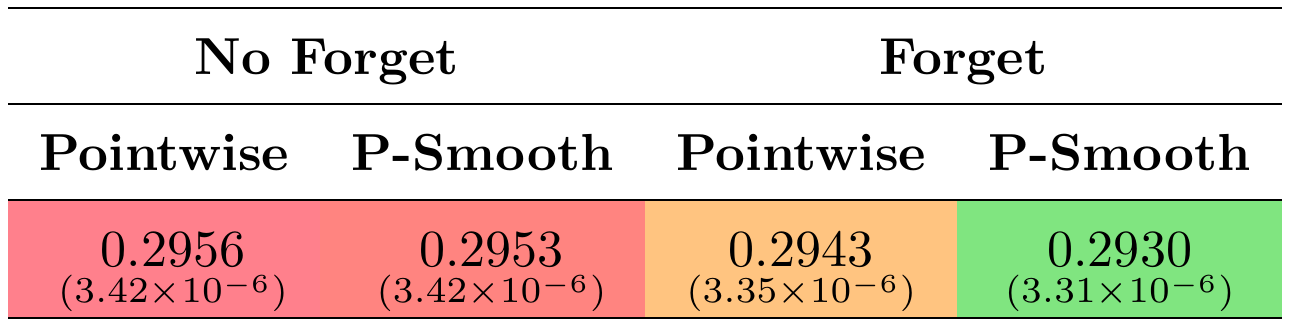

\[\begin{align*} Y_t &\sim \mathcal{N}\left(\frac{\sin(0.005 \pi t )}{2},\,1\right) \\ \widehat{X}_{t,1} &\sim \widehat{F}_{1} = \mathcal{N}(-1,\,1) \\ \widehat{X}_{t,2} &\sim \widehat{F}_{2} = \mathcal{N}(3,\,4) \end{align*}\]

Changing optimal weights

Single run example depicted aside

No forgetting leads to long-term constant weights

Data:

Combination methods:

Tuning paramter grids:

Simple exponential smoothing with additive errors (ETS-ANN):

\[\begin{align*} Y_{t} = l_{t-1} + \varepsilon_t \quad \text{with} \quad l_t = l_{t-1} + \alpha \varepsilon_t \quad \text{and} \quad \varepsilon_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigma^2) \end{align*}\]

Quantile regression (QuantReg): For each \(p \in \mathcal{P}\) we assume:

\[\begin{align*} F^{-1}_{Y_t}(p) = \beta_{p,0} + \beta_{p,1} Y_{t-1} + \beta_{p,2} |Y_{t-1}-Y_{t-2}| \end{align*}\]

ARIMA(1,0,1)-GARCH(1,1) with Gaussian errors (ARMA-GARCH):

\[\begin{align*} Y_{t} = \mu + \phi(Y_{t-1}-\mu) + \theta \varepsilon_{t-1} + \varepsilon_t \quad \text{with} \quad \varepsilon_t = \sigma_t Z, \quad \sigma_t^2 = \omega + \alpha \varepsilon_{t-1}^2 + \beta \sigma_{t-1}^2 \quad \text{and} \quad Z_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1) \end{align*}\]

ARIMA(0,1,0)-I-EGARCH(1,1) with Gaussian errors (I-EGARCH):

\[\begin{align*} Y_{t} = \mu + Y_{t-1} + \varepsilon_t \quad \text{with} \quad \varepsilon_t = \sigma_t Z, \quad \log(\sigma_t^2) = \omega + \alpha Z_{t-1}+ \gamma (|Z_{t-1}|-\mathbb{E}|Z_{t-1}|) + \beta \log(\sigma_{t-1}^2) \quad \text{and} \quad Z_t \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1) \end{align*}\]

ARIMA(0,1,0)-GARCH(1,1) with student-t errors (I-GARCHt):

\[\begin{align*} Y_{t} = \mu + Y_{t-1} + \varepsilon_t \quad \text{with} \quad \varepsilon_t = \sigma_t Z, \quad \sigma_t^2 = \omega + \alpha \varepsilon_{t-1}^2 + \beta \sigma_{t-1}^2 \quad \text{and} \quad Z_t \sim t(0,1, \nu) \end{align*}\]

| ETS | QuantReg | ARMA-GARCH | I-EGARCH | I-GARCHt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.101(>.999) | 1.358(>.999) | 0.52(0.993) | 0.511(0.999) | -0.037(0.406) |

| BOAG | EWAG | ML-PolyG | BMA | QRlin | QRconv | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pointwise | -0.170(0.055) | -0.089(0.175) | -0.141(0.112) | 0.032(0.771) | 3.482(>.999) | -0.019(0.309) |

| B-Constant | -0.118(0.146) | -0.049(0.305) | -0.090(0.218) | 0.038(0.834) | 4.002(>.999) | 0.539(0.996) |

| P-Constant | -0.138(0.020) | -0.070(0.137) | -0.133(0.026) | 0.039(0.851) | 5.275(>.999) | 0.009(0.683) |

| B-Smooth | -0.173(0.062) | -0.065(0.276) | -0.141(0.118) | -0.042(0.386) | - | - |

| P-Smooth | -0.182(0.039) | -0.107(0.121) | -0.160(0.065) | 0.040(0.804) | 3.495(>.999) | -0.012(0.369) |

CRPS difference to Naive. Negative values correspond to better performance (the best value is bold).

Additionally, we show the p-value of the DM-test, testing against Naive. The cells are colored with respect to their values (the greener better).

Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2024). International Journal of Forecasting, 40(4), 1568-1586.

We extend the B-Smooth and P-Smooth procedures to the multivariate setting:

Let \(\boldsymbol{\psi}^{\text{mv}}=(\psi_1,\ldots, \psi_{D})\) and \(\boldsymbol{\psi}^{\text{pr}}=(\psi_1,\ldots, \psi_{P})\) be two sets of bounded basis functions on \((0,1)\):

\[\begin{equation*} \boldsymbol w_{t,k} = \boldsymbol{\psi}^{\text{mv}} \boldsymbol{b}_{t,k} {\boldsymbol{\psi}^{pr}}' \end{equation*}\]

with parameter matix \(\boldsymbol b_{t,k}\). The latter is estimated to penalize \(L_2\)-smoothing which minimizes

\[\begin{align} & \| \boldsymbol{\beta}_{t,d, k}' \boldsymbol{\varphi}^{\text{pr}} - \boldsymbol b_{t, d, k}' \boldsymbol{\psi}^{\text{pr}} \|^2_2 + \lambda^{\text{pr}} \| \mathcal{D}_{q} (\boldsymbol b_{t, d, k}' \boldsymbol{\psi}^{\text{pr}}) \|^2_2 + \nonumber \\ & \| \boldsymbol{\beta}_{t, p, k}' \boldsymbol{\varphi}^{\text{mv}} - \boldsymbol b_{t, p, k}' \boldsymbol{\psi}^{\text{mv}} \|^2_2 + \lambda^{\text{mv}} \| \mathcal{D}_{q} (\boldsymbol b_{t, p, k}' \boldsymbol{\psi}^{\text{mv}}) \|^2_2 \nonumber \end{align}\]

with differential operator \(\mathcal{D}_q\) of order \(q\)

We have an analytical solution.

Linear combinations of bounded basis functions:

\[\begin{equation} \underbrace{\boldsymbol w_{t,k}}_{D \text{ x } P} = \sum_{j=1}^{\widetilde D} \sum_{l=1}^{\widetilde P} \beta_{t,j,l,k} \varphi^{\text{mv}}_{j} \varphi^{\text{pr}}_{l} = \underbrace{\boldsymbol \varphi^{\text{mv}}}_{D\text{ x }\widetilde D} \boldsymbol \beta_{t,k} \underbrace{{\boldsymbol\varphi^{\text{pr}}}'}_{\widetilde P \text{ x }P} \nonumber \end{equation}\]

A popular choice: B-Splines

\(\boldsymbol \beta_{t,k}\) is calculated using a reduced regret matrix:

\(\underbrace{\boldsymbol r_{t,k}}_{\widetilde P \times \widetilde D} = \boldsymbol \varphi^{\text{pr}} \underbrace{\left({\boldsymbol{QL}}_{\mathcal{P}}^{\nabla}(\widetilde{\boldsymbol X}_{t},Y_t)- {\boldsymbol{QL}}_{\mathcal{P}}^{\nabla}(\widehat{\boldsymbol X}_{t},Y_t)\right)}_{\text{PxD}}\boldsymbol \varphi^{\text{mv}}\)

If \(\widetilde P = P\) it holds that \(\boldsymbol \varphi^{pr} = \boldsymbol{I}\) (pointwise)

For \(\widetilde P = 1\) we receive constant weights

Evaluation: Exclude first 182 observations

Extensions: Penalized smoothing | Forgetting

Tuning strategies:

Computation Time: ~30 Minutes

| JSU1 | JSU2 | JSU3 | JSU4 | Norm1 | Norm2 | Norm3 | Norm4 | Naive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.487 | 1.444 | 1.499 | 1.374 | 1.414 | 1.535 | 1.420 | 1.422 | 1.295 |

| Description | Parameter Tuning | BOA | ML-Poly | EWA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.2933 | 1.2966 | 1.3188 | |

| Pointwise | 1.2936 | 1.3010 | 1.3101 | |

| FTL | 1.3752 | 1.3692 | 1.3863 | |

| B Constant Pr | 1.2936 | 1.3000 | 1.3432 | |

| B Constant Mv | 1.2918 | 1.2945 | 1.3076 | |

| Forget | Bayesian Fix | 1.2930 | 1.2956 | 1.3096 |

| Full | Bayesian Fix | 1.2905 | 1.2902 | 1.2870. |

| Smooth.forget | Bayesian Fix | 1.2911 | 1.2912 | 1.2869. |

| Smooth | Bayesian Fix | 1.2918 | 1.2917 | 1.2873. |

| Forget | Bayesian Online | 1.2855** | 1.2961 | 1.3098 |

| Full | Bayesian Online | 1.2919 | 1.2873. | 1.2873. |

| Smooth.forget | Bayesian Online | 1.2845** | 1.2862* | 1.2864. |

| Smooth | Bayesian Online | 1.2918 | 1.2918 | 1.2874. |

| Forget | Sampling Online | 1.2855** | 1.2961 | 1.3114 |

| Full | Sampling Online | 1.2886 | 1.2861* | 1.2873. |

| Smooth.forget | Sampling Online | 1.2845*** | 1.2867* | 1.2866. |

| Smooth | Sampling Online | 1.2918 | 1.2917 | 1.2877. |

function updateChartInner(g, x, y, linesGroup, color, line, data) {

// Update axes with transitions

x.domain([0, d3.max(data, d => d.x)]);

g.select(".x-axis").transition().duration(1500).call(d3.axisBottom(x).ticks(10));

y.domain([0, d3.max(data, d => d.y)]);

g.select(".y-axis").transition().duration(1500).call(d3.axisLeft(y).ticks(5));

// Group data by basis function

const dataByFunction = Array.from(d3.group(data, d => d.b));

const keyFn = d => d[0];

// Update basis function lines

const u = linesGroup.selectAll("path").data(dataByFunction, keyFn);

u.join(

enter => enter.append("path").attr("fill","none").attr("stroke-width",3)

.attr("stroke", (_, i) => color(i)).attr("d", d => line(d[1].map(pt => ({x: pt.x, y: 0}))))

.style("opacity",0),

update => update,

exit => exit.transition().duration(1000).style("opacity",0).remove()

)

.transition().duration(1000)

.attr("d", d => line(d[1]))

.attr("stroke", (_, i) => color(i))

.style("opacity",1);

}

chart = {

// State variables for selected parameters

let selectedMu = 0.5;

let selectedSig = 1;

let selectedNonc = 0;

let selectedTailw = 1;

const filteredData = () => bsplineData.filter(d =>

Math.abs(selectedMu - d.mu) < 0.001 &&

d.sig === selectedSig &&

d.nonc === selectedNonc &&

d.tailw === selectedTailw

);

const container = d3.create("div")

.style("max-width", "none")

.style("width", "100%");;

const controlsContainer = container.append("div")

.style("display", "flex")

.style("gap", "20px");

// slider controls

const sliders = [

{ label: 'Mu', get: () => selectedMu, set: v => selectedMu = v, min: 0.1, max: 0.9, step: 0.2 },

{ label: 'Sigma', get: () => Math.log2(selectedSig), set: v => selectedSig = 2 ** v, min: -2, max: 2, step: 1 },

{ label: 'Noncentrality', get: () => selectedNonc, set: v => selectedNonc = v, min: -4, max: 4, step: 2 },

{ label: 'Tailweight', get: () => Math.log2(selectedTailw), set: v => selectedTailw = 2 ** v, min: -2, max: 2, step: 1 }

];

// Build slider controls with D3 data join

const sliderCont = controlsContainer.selectAll('div').data(sliders).join('div')

.style('display','flex').style('align-items','center').style('gap','10px')

.style('flex','1').style('min-width','0px');

sliderCont.append('label').text(d => d.label + ':').style('font-size','20px');

sliderCont.append('input')

.attr('type','range').attr('min', d => d.min).attr('max', d => d.max).attr('step', d => d.step)

.property('value', d => d.get())

.on('input', function(event, d) {

const val = +this.value; d.set(val);

d3.select(this.parentNode).select('span').text(d.label.match(/Sigma|Tailweight/) ? 2**val : val);

updateChart(filteredData());

})

.style('width', '100%');

sliderCont.append('span').text(d => (d.label.match(/Sigma|Tailweight/) ? d.get() : d.get()))

.style('font-size','20px');

// Add Reset button to clear all sliders to their defaults

controlsContainer.append('button')

.text('Reset')

.style('font-size', '20px')

.style('align-self', 'center')

.style('margin-left', 'auto')

.on('click', () => {

// reset state vars

selectedMu = 0.5;

selectedSig = 1;

selectedNonc = 0;

selectedTailw = 1;

// update input positions

sliderCont.selectAll('input').property('value', d => d.get());

// update displayed labels

sliderCont.selectAll('span')

.text(d => d.label.match(/Sigma|Tailweight/) ? (2**d.get()) : d.get());

// redraw chart

updateChart(filteredData());

});

// Build SVG

const width = 1200;

const height = 450;

const margin = {top: 40, right: 20, bottom: 40, left: 40};

const innerWidth = width - margin.left - margin.right;

const innerHeight = height - margin.top - margin.bottom;

// Set controls container width to match SVG plot width

controlsContainer.style("max-width", "none").style("width", "100%");

// Distribute each control evenly and make sliders full-width

controlsContainer.selectAll("div").style("flex", "1").style("min-width", "0px");

controlsContainer.selectAll("input").style("width", "100%").style("box-sizing", "border-box");

// Create scales

const x = d3.scaleLinear()

.domain([0, 1])

.range([0, innerWidth]);

const y = d3.scaleLinear()

.domain([0, 1])

.range([innerHeight, 0]);

// Create a color scale for the basis functions

const color = d3.scaleOrdinal(d3.schemeCategory10);

// Create SVG

const svg = d3.create("svg")

.attr("width", "100%")

.attr("height", "auto")

.attr("viewBox", [0, 0, width, height])

.attr("preserveAspectRatio", "xMidYMid meet")

.attr("style", "max-width: 100%; height: auto;");

// Create the chart group

const g = svg.append("g")

.attr("transform", `translate(${margin.left},${margin.top})`);

// Add axes

const xAxis = g.append("g")

.attr("transform", `translate(0,${innerHeight})`)

.attr("class", "x-axis")

.call(d3.axisBottom(x).ticks(10))

.style("font-size", "20px");

const yAxis = g.append("g")

.attr("class", "y-axis")

.call(d3.axisLeft(y).ticks(5))

.style("font-size", "20px");

// Add a horizontal line at y = 0

g.append("line")

.attr("x1", 0)

.attr("x2", innerWidth)

.attr("y1", y(0))

.attr("y2", y(0))

.attr("stroke", "#000")

.attr("stroke-opacity", 0.2);

// Add gridlines

g.append("g")

.attr("class", "grid-lines")

.selectAll("line")

.data(y.ticks(5))

.join("line")

.attr("x1", 0)

.attr("x2", innerWidth)

.attr("y1", d => y(d))

.attr("y2", d => y(d))

.attr("stroke", "#ccc")

.attr("stroke-opacity", 0.5);

// Create a line generator

const line = d3.line()

.x(d => x(d.x))

.y(d => y(d.y))

.curve(d3.curveBasis);

// Group to contain the basis function lines

const linesGroup = g.append("g")

.attr("class", "basis-functions");

// Store the current basis functions for transition

let currentBasisFunctions = new Map();

// Function to update the chart with new data

function updateChart(data) {

updateChartInner(g, x, y, linesGroup, color, line, data);

}

// Store the update function

svg.node().update = updateChart;

// Initial render

updateChart(filteredData());

container.node().appendChild(svg.node());

return container.node();

}Non-central beta distribution Johnson et al. (1995):

\[\begin{equation*} \mathcal{B}(x, a, b, c) = \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} e^{-c/2} \frac{\left( \frac{c}{2} \right)^j}{j!} I_x \left( a + j , b \right) \end{equation*}\]

Penalty and \(\lambda\) need to be adjusted accordingly Li & Cao (2022)

Using non equidistant knots in profoc is straightforward:

Basis specification b_smooth_pr is internally passed to make_basis_mats().

Profoc adjusts penatly and \(\lambda\)

Potential Downsides:

Important:

Upsides:

The profoc R Package:

Pubications:

Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2023). CRPS learning. Journal of Econometrics, 237(2), 105221.

Berrisch, J., & Ziel, F. (2024). Multivariate probabilistic CRPS learning with an application to day-ahead electricity prices. International Journal of Forecasting, 40(4), 1568-1586.

Berrisch, J., Pappert, S., Ziel, F., & Arsova, A. (2023). Finance Research Letters, 52, 103503.

Understanding European Allowances (EUA) dynamics is important for several fields:

Portfolio & Risk Management,

Sustainability Planing

Political decisions

EUA prices are obviously connected to the energy market

How can the dynamics be characterized?

Several Questions arise:

EUA, natural gas, Brent crude oil, coal

March 15, 2010, until October 14, 2022

Data was normalized w.r.t. \(\text{CO}_2\) emissions

Emission-adjusted prices reflects one tonne of \(\text{CO}_2\)

We adjusted for inflation by Eurostat’s HICP, excluding energy

Log transformation of the data to stabilize the variance

ADF Test: All series are stationary in first differences

Johansen’s likelihood ratio trace test suggests two cointegrating relationships (levels)

Johansen’s likelihood ratio trace test suggests no cointegrating relationships (logs)

Sklars theorem: decompose target into - marginal distributions: \(F_{X_{k,t}|\mathcal{F}_{t-1}}\) for \(k=1,\ldots, K\), and - copula function: \(C_{\boldsymbol{U}_{t}|\mathcal{F}_{t - 1}}\)

Let \(\boldsymbol{x}_t= (x_{1,t},\ldots, x_{K,t})^\intercal\) be the realized values

It holds that:

\[\begin{align} F_{\boldsymbol{X}_t|\mathcal{F}_{t-1}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) = C_{\boldsymbol{U}_{t}|\mathcal{F}_{t - 1}}(\boldsymbol{u}_t) \nonumber \end{align}\]

with: \(\boldsymbol{u}_t =(u_{1,t},\ldots, u_{K,t})^\intercal\), \(u_{k,t} = F_{X_{k,t}|\mathcal{F}_{t-1}}(x_{k,t})\)

For brewity we drop the conditioning on \(\mathcal{F}_{t-1}\).

The model can be specified as follows

\[\begin{align} F(\boldsymbol{x}_t) = C \left[\mathbf{F}(\boldsymbol{x}_t; \boldsymbol{\mu}_t, \boldsymbol{ \sigma }_{t}^2, \boldsymbol{\nu}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}); \Xi_t, \Theta\right] \nonumber \end{align}\]

\(\Xi_{t}\) denotes time-varying dependence parameters \(\Theta\) denotes time-invariant dependence parameters

We take \(C\) as the \(t\)-copula

\[\mathbf{F} = (F_1, \ldots, F_K)^{\intercal}\]

\[\begin{align} \Delta \boldsymbol{\mu}_t = \Pi \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} + \Gamma \Delta \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} \nonumber \end{align}\]

where \(\Pi = \alpha \beta^{\intercal}\) is the cointegrating matrix of rank \(r\), \(0 \leq r\leq K\).

\[\begin{align} \sigma_{i,t}^2 = & \omega_i + \alpha^+_{i} (\epsilon_{i,t-1}^+)^2 + \alpha^-_{i} (\epsilon_{i,t-1}^-)^2 + \beta_i \sigma_{i,t-1}^2 \nonumber \end{align}\]

where \(\epsilon_{i,t-1}^+ = \max\{\epsilon_{i,t-1}, 0\}\) …

Separate coefficients for positive and negative innovations to capture leverage effects.

\[\begin{align*} \Xi_{t} = & \Lambda\left(\boldsymbol{\xi}_{t}\right) \\ \xi_{ij,t} = & \eta_{0,ij} + \eta_{1,ij} \xi_{ij,t-1} + \eta_{2,ij} z_{i,t-1} z_{j,t-1}, \end{align*}\]

\(\xi_{ij,t}\) is a latent process

\(z_{i,t}\) denotes the \(i\)-th standardized residual from time series \(i\) at time point \(t\)

\(\Lambda(\cdot)\) is a link function - ensures that \(\Xi_{t}\) is a valid variance covariance matrix - ensures that \(\Xi_{t}\) does not exceed its support space and remains semi-positive definite

All parameters can be estimated jointly. Using conditional independence: \[\begin{align*} L = f_{X_1} \prod_{i=2}^T f_{X_i|\mathcal{F}_{i-1}}, \end{align*}\] with multivariate conditional density: \[\begin{align*} f_{\mathbf{X}_t}(\mathbf{x}_t | \mathcal{F}_{t-1}) = c\left[\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{x}_t;\boldsymbol{\mu}_t, \boldsymbol{\sigma}_{t}^2, \boldsymbol{\nu}, \boldsymbol{\lambda});\Xi_t, \Theta\right] \cdot \\ \prod_{i=1}^K f_{X_{i,t}}(\mathbf{x}_t;\boldsymbol{\mu}_t, \boldsymbol{\sigma}_{t}^2, \boldsymbol{\nu}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}) \end{align*}\] The copula density \(c\) can be derived analytically.

=> 2227 potential starting points

We sample 250 to reduce computational cost

We draw \(2^{12}= 2048\) trajectories from the joint predictive distribution

Forecasts are evaluated by the energy score (ES)

\[\begin{align*} \text{ES}_t(F, \mathbf{x}_t) = \mathbb{E}_{F} \left(||\tilde{\mathbf{X}}_t - \mathbf{x}_t||_2\right) - \\ \frac{1}{2} \mathbb{E}_F \left(||\tilde{\mathbf{X}}_t - \tilde{\mathbf{X}}_t'||_2 \right) \end{align*}\]

where \(\mathbf{x}_t\) is the observed \(K\)-dimensional realization and \(\tilde{\mathbf{X}}_t\), respectively \(\tilde{\mathbf{X}}_t'\) are independent random vectors distributed according to \(F\)

For univariate cases the Energy Score becomes the Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS)

Relative improvement in ES compared to \(\text{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}\)

Cellcolor: w.r.t. test statistic of Diebold-Mariano test (testing wether the model outperformes the benchmark, greener = better).

| Model | \(\text{ES}^{\text{All}}_{1-30}\) | \(\text{ES}^{\text{EUA}}_{1-30}\) | \(\text{ES}^{\text{Oil}}_{1-30}\) | \(\text{ES}^{\text{NGas}}_{1-30}\) | \(\text{ES}^{\text{Coal}}_{1-30}\) | \(\text{ES}^{\text{All}}_{1}\) | \(\text{ES}^{\text{All}}_{5}\) | \(\text{ES}^{\text{All}}_{30}\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\) | 161.96 | 10.06 | 37.94 | 146.73 | 13.22 | 5.56 | 13.28 | 34.29 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma_t, \rho_t}_{}\) | 9.40 | 3.75 | -0.41 | 11.39 | 4.13 | 10.34 | 9.10 | 7.59 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho_t}_{\textrm{ncp}, \textrm{log}}\) | 12.04 | 6.16 | -0.56 | 14.33 | 7.35 | 9.22 | 9.82 | 10.02 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{\textrm{log}}\) | 12.10 | 6.25 | -0.59 | 14.44 | 7.31 | 9.04 | 9.66 | 9.91 |

| \(\textrm{VECM}^{\textrm{r0}, \sigma_t, \rho_t}_{\textrm{lev}, \textrm{ncp}}\) | 9.68 | -0.72 | 0.32 | 11.74 | 3.70 | 10.82 | 10.50 | 8.21 |

| \(\textrm{VECM}^{\textrm{r0}, \sigma, \rho_t}_{\textrm{log}}\) | 12.15 | 6.10 | -0.70 | 14.57 | 7.80 | 8.05 | 9.99 | 10.04 |

| \(\textrm{ETS}^{\sigma}\) | 9.94 | 5.75 | 0.08 | 13.05 | 7.83 | 6.96 | 7.74 | 6.21 |

| \(\textrm{ETS}^{\sigma}_{\textrm{log}}\) | 8.12 | 7.80 | -0.51 | 11.17 | 8.54 | 5.05 | 6.14 | 2.66 |

| \(\textrm{VES}^{\sigma}\) | 5.50 | -4.43 | -3.22 | 6.29 | 4.68 | -25.99 | -2.42 | 3.07 |

| \(\textrm{VES}^{\sigma}_{\textrm{log}}\) | 7.68 | 3.31 | -4.34 | 9.07 | 8.30 | -22.11 | 1.07 | 4.32 |

Improvement in CRPS of selected models relative to \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\) in % (higher = better). Colored according to the test statistic of a DM-Test comparing to \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\) (greener means lower test statistic i.e., better performance compared to \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\)).

EUA

|

Oil

|

NGas

|

Coal

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | H1 | H5 | H30 | H1 | H5 | H30 | H1 | H5 | H30 | H1 | H5 | H30 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\) | 0.4 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 9.1 | 4.7 | 11.6 | 29.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.8 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma_t, \rho_t}_{}\) | 5.6 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.7 | -0.8 | 12.6 | 10.5 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 6.5 | 2.1 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho_t}_{\textrm{ncp}, \textrm{log}}\) | 5.1 | 8.7 | 5.0 | 0.7 | 0.8 | -0.4 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 12.4 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 6.7 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{\textrm{log}}\) | 4.7 | 8.9 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | -0.6 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 12.4 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 6.6 |

| \(\textrm{VECM}^{\textrm{r0}, \sigma_t, \rho_t}_{\textrm{lev}, \textrm{ncp}}\) | 3.6 | 0.6 | -1.6 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 13.1 | 12.2 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 7.2 | 1.5 |

| \(\textrm{VECM}^{\textrm{r0}, \sigma, \rho_t}_{\textrm{log}}\) | 4.2 | 8.9 | 5.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | -0.8 | 9.9 | 11.8 | 12.7 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 7.3 |

| \(\textrm{ETS}^{\sigma}\) | 0.2 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 1.1 | 0.9 | -0.2 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 7.5 | 6.7 | 5.6 |

| \(\textrm{ETS}^{\sigma}_{\textrm{log}}\) | 1.0 | 8.6 | 8.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | -0.6 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 7.1 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 6.7 |

| \(\textrm{VES}^{\sigma}\) | -38.5 | -6.4 | -5.4 | -33.3 | -6.1 | -2.4 | -26.6 | -2.6 | 3.6 | -37.5 | -5.5 | 4.7 |

| \(\textrm{VES}^{\sigma}_{\textrm{log}}\) | -32.4 | 2.8 | 1.8 | -30.4 | -6.2 | -3.2 | -22.0 | 1.8 | 5.4 | -27.0 | 2.3 | 6.4 |

RMSE measures the performance of the forecasts at their mean

Conclusion: the Improvements seen before must be attributed to other parts of the multivariate probabilistic predictive distribution

Improvement in RMSE score of selected models relative to \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\) in % (higher = better). Colored according to the test statistic of a DM-Test comparing to \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\) (greener means lower test statistic i.e., better performance compared to \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\)).

EUA

|

Oil

|

NGas

|

Coal

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | H1 | H5 | H30 | H1 | H5 | H30 | H1 | H5 | H30 | H1 | H5 | H30 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{}\) | 0.9 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2.9 | 6.4 | 16.7 | 17.8 | 42.8 | 85.4 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 7.0 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma_t, \rho_t}_{}\) | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | -0.3 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0.3 | 1.3 | -0.2 | 0.0 | -1.8 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho_t}_{\textrm{ncp}, \textrm{log}}\) | -270.5 | -154.1 | -139.9 | 0.5 | -0.5 | -2.9 | -0.8 | 0.7 | -1.6 | 0.3 | -31.2 | -24.5 |

| \(\textrm{RW}^{\sigma, \rho}_{\textrm{log}}\) | -705.0 | -265.4 | -125.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | -0.2 | -0.4 | 0.1 | -1.6 | -0.9 | -0.3 | -8.3 |

| \(\textrm{VECM}^{\textrm{r0}, \sigma_t, \rho_t}_{\textrm{lev}, \textrm{ncp}}\) | -0.9 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | -0.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| \(\textrm{VECM}^{\textrm{r0}, \sigma, \rho_t}_{\textrm{log}}\) | -271.5 | -191.3 | -114.3 | 1.7 | -12.3 | -3.6 | -0.6 | 1.6 | -4.1 | 0.0 | -0.8 | -6.7 |

| \(\textrm{ETS}^{\sigma}\) | -0.3 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.2 | -2.4 | -3.9 | 2.5 |

| \(\textrm{ETS}^{\sigma}_{\textrm{log}}\) | -1.0 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.0 | -0.1 | -1.9 | -1.9 | -13.9 | -0.3 | -3.6 | -1.8 |

| \(\textrm{VES}^{\sigma}\) | -37.4 | -8.9 | -6.0 | -27.9 | -7.4 | -2.8 | -27.2 | -9.5 | -2.4 | -41.7 | -1.2 | 1.6 |

| \(\textrm{VES}^{\sigma}_{\textrm{log}}\) | -37.6 | -9.2 | -7.8 | -26.8 | -7.3 | -3.0 | -27.0 | -6.8 | -3.5 | -41.2 | -2.2 | -0.3 |

Accounting for heteroscedasticity or stabilizing the variance via log transformation is crucial for good performance in terms of ES

Theoretical

Probabilistic Online Learning:

Aggregation

Regression

Practical

Applications

Energy Commodities

Electricity Prices

Electricity Load

Well received by the academic community:

of papers already published

104 citations since 2020 (Google Scholar)

Software

R Packages:

Python Packages:

Contributions to other projects:

RcppArmadillo

gamlss

NixOS/nixpkgs

OpenPrinting/foomatic-db

Awards:

Berrisch, J., Narajewski, M., & Ziel, F. (2023):

Won Western Power Distribution Competition

Won Best-Student-Presentation Award